Last week, I wrote about my sister's search for a basic, comfortable roadbike and in the post I explained that she is looking for a "normal" bike - That is, for a bike that is neither vintage, nor classic, nor lugged, nor artisanal - just a regular bike in the sense that one could walk into a bicycle shop off the street and buy it for a reasonable price. Once again I thank you all for the feedback, which was immensely helpful, and I will post an update regarding what bike she ends up getting. But on a separate note, I was intrigued by the category of replies that "pathologized" the way I described my sister's criteria - a few even questioning whether she ought to be buying a bike at all under the circumstances. Those comments made me think about expectations when it comes to bicycle shopping. And frankly, I think that "we" - i.e. those of us who are "into" bicycles, and especially into classic and vintage bicycles - can be out of touch with what people who "just want a bike" expect. Here are some of my observations about first time bike buyers' expectations that I've gathered from personal conversations and reader emails over the past two years:

It's too complicated

I think it is accurate to say that most people off to buy their first bicycle as an adult initially expect for the experience to be fairly simple. They envision being able to walk into a bike shop, to ask for some advice, and to walk out with a nice shiny bike. And I don't think that this attitude makes them "lazy" or "not committed to cycling." I think it is an entirely normal and healthy attitude. Unfortunately, hopes for simplicity are all too frequently crushed as bicycle shopping turns frustrating. The bicycles suggested at bike shops are often uncomfortable or otherwise unappealing, and the customer does not know how to express what exactly does not feel right. Purchasing a bicycle should be simple. But I believe that both bicycle shops and the industry at large are out of touch with what customers actually need.

It's too expensive

The fact is, that those of us who enjoy customising bicycles, building up bicycles from the frame up, hunting for rare parts and refurbishing vintage bikes, seeking out unique and unusual bicycles that are only available in specialty shops, and so on... are not in the majority, and I think we need to respect that. Most people - even those who are excited about cycling - just want to go to a "regular" bike shop, buy a bike, ride it without problems, and fiddle as little with it as possible. There is nothing wrong with that, and I think it would be misguided of me to try and convince everyone I meet that my preferences are "better." And in fact I don't think they are better; they are just different.

I would venture to say that a large percentage of would-be cyclists in North America are turned off from cycling by the discrepancy between their expectations and their actual experiences, when it comes to buying their first bicycle. And it seems to me that rather than blame the "victim," it would be more useful to rethink how the bicycle industry approaches potential customers. I have spoken to way too many people at this point who've told me that they'd love to cycle but are having terrible luck finding a bike. And that just isn't right.

It's too complicated

I think it is accurate to say that most people off to buy their first bicycle as an adult initially expect for the experience to be fairly simple. They envision being able to walk into a bike shop, to ask for some advice, and to walk out with a nice shiny bike. And I don't think that this attitude makes them "lazy" or "not committed to cycling." I think it is an entirely normal and healthy attitude. Unfortunately, hopes for simplicity are all too frequently crushed as bicycle shopping turns frustrating. The bicycles suggested at bike shops are often uncomfortable or otherwise unappealing, and the customer does not know how to express what exactly does not feel right. Purchasing a bicycle should be simple. But I believe that both bicycle shops and the industry at large are out of touch with what customers actually need.

It's too expensive

I receive lots of emails from people looking to buy their first bike, and the figure $500 comes up over and over again as the upper limit of their budget - regardless of how well off the person is. While that expectation is unrealistic, I think that from the customer's point of view - assuming that they are not familiar with the industry - it is reasonable. Once they get to know the market a little better, chances are that they will come to terms with spending considerably more on a bike than they initially expected to. I blame this discrepancy on the industry and not on the customer being "cheap." In theory, large manufacturers could churn out attractive and functional bikes for $500, but for a variety of reasons, they do not.

I don't want to be a bike expert, I just want to ride

I hear this one repeatedly, and I agree. Wanting to buy a bike should not require one to become an expert in bikes first. There is a difference between cycling and being "into bicycles," and it is perfectly normal to be the former without becoming the latter.

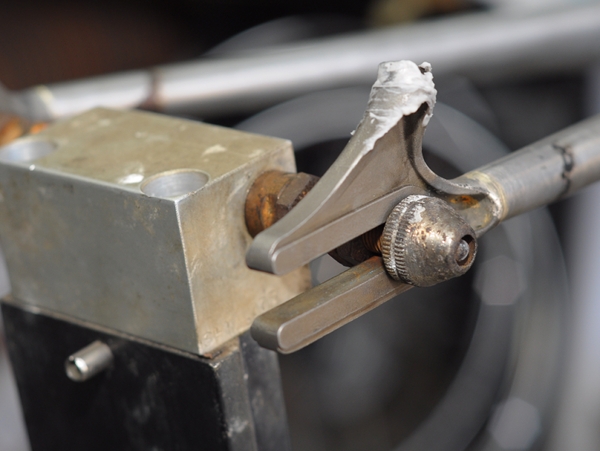

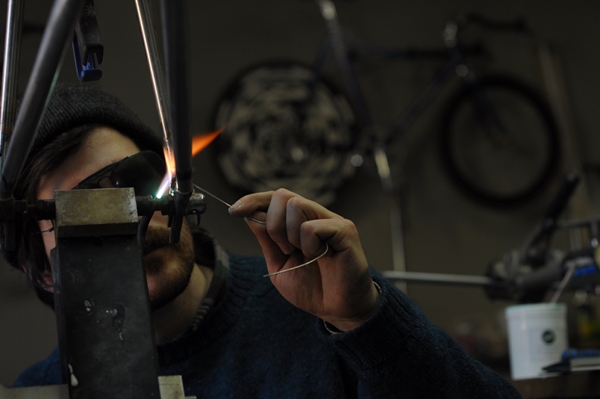

The fact is, that those of us who enjoy customising bicycles, building up bicycles from the frame up, hunting for rare parts and refurbishing vintage bikes, seeking out unique and unusual bicycles that are only available in specialty shops, and so on... are not in the majority, and I think we need to respect that. Most people - even those who are excited about cycling - just want to go to a "regular" bike shop, buy a bike, ride it without problems, and fiddle as little with it as possible. There is nothing wrong with that, and I think it would be misguided of me to try and convince everyone I meet that my preferences are "better." And in fact I don't think they are better; they are just different.

I would venture to say that a large percentage of would-be cyclists in North America are turned off from cycling by the discrepancy between their expectations and their actual experiences, when it comes to buying their first bicycle. And it seems to me that rather than blame the "victim," it would be more useful to rethink how the bicycle industry approaches potential customers. I have spoken to way too many people at this point who've told me that they'd love to cycle but are having terrible luck finding a bike. And that just isn't right.

12:43

12:43

kaniamazdar

kaniamazdar